Interview for the Cinéma du réel

festival

Stella came to France to try and save her

very ill husband. They come from the working class that post-communist

Romania no longer values and has left behind. Forced to beg in

order to survive, enduring endless waiting and hospitals, and

resigned to her fate, Stella fights back.

Christine André: What was the

starting point of your film?

Vanina Vignal: It is my connections with Romania, which go back

a long way. I’ve been going back and forth for the past

fifteen years, working on different jobs, and it has become my

second country. I then had the opportunity to work as assistant

to a director who was making a film about Romanies and French

institutions, which enabled me to go into the shantytowns in the

Parisian suburbs, and that’s where I met Stella.

How did Stella impose herself on you?

When I was working as the director’s assistant, I realized

that he was making a film that didn’t interest me at all.

I saw different things than the subjects he was treating, I wanted

to go in a different direction, and meeting Stella gave me the

idea to make this film. I understood that, thanks to her, I could

talk about these people that we very rarely actually meet because

I was lucky enough to come into her life at the right time: she

wanted to talk to someone from out of her environment and escape

a little from the “shantytown-husband-begging” circle.

She was very depressed with the way her life had turned and she

was in great need of a “friend”. Of course, the fact

that I speak Romanian made it easier.

Being Romanian, Stella and Marcel are

stigmatized as Romanies and beggars. How did you tackle that?

These people are very often stereotyped in films about Romanies,

or Gypsies. Apart from the film Caravane 55 (by Valérie

Mitteaux and Anna Pitoun), Romanies are crystallized in an extremely

negative image. However, I have met many Romanies from the working

class, who are not necessarily Gypsies, like Stella, and I’ve

seen people trying to make something of their lives, who dream

of settling down and integrating well in a country, though not

necessarily through deliberate choice but because they can’t

find work in their own country and emigration represents hope

of a better life. In my mind, they are economic immigrants like

so many others, no better and no worse. What is more, when Stella

arrived in France, she really believed she would find a job. She

worked for a while as a babysitter, paid cash in hand, she went

to the local job centre, tried to find work as a cleaning lady,

but people from shantytowns inspire fear: people think straight

away of the mafia and criminal rings. I wanted to film people

who live quiet lives, like children coming back from school, those

who stay in the background, avoiding stereotypes like thieving

Romanies or quaint Gypsy musicians. I didn’t want too many

characters present so that we could really get to know them. During

editing, we tried to translate what I had filmed as simply as

possible, without putting words in their mouths, and especially

without adding stylistic effects.

Is there a political dimension in your

film?

I wanted to broach politics but keep it in the background. We

learn that Stella represents Eastern immigrants from the working

class. Many of these blue-collar workers still haven’t grasped

the meaning of the 1989 revolution, their world tumbled around

them and no one has explained the new rules to go by. This new

ultra liberal society doesn’t take care of Romanies, old-age

pensioners, the poor or the sick. Many people have been dumped

along the way and have no chance of finding work. In Romania,

one of the only unqualified jobs left is working in the fields,

paid just one or two euros a day. Gabi, Stella’s sister,

worked like that but she didn’t earn enough to feed her

three children. If she begs in Paris, she can get between two

and ten euros a day, and so feeding her family that has stayed

in Romania. Before making the film, I didn’t really understand

the nostalgia for the totalitarian communist period. But during

that period, every worker had a job, a roof over their heads,

holidays and a social position.

Throughout the film, we feel the complicity

between the two of you.

I spent a lot of time with her, both with and without the camera,

sharing such a lot. I wanted the spectators to meet Stella, Marcel

and all the others, just as I met them. I wanted to film them

in all their normality, in their humdrum everyday life. She grasped

the importance of my project and accepted to go along with it

because she considered me, above all, as a friend. She didn’t

really know what to expect but she didn’t try to control

her image. She trusted me.

How did you go about filming her begging,

which she quite simply analyses?

One day, when she was feeling really fed up, Stella talked to

me about begging. She was on her last legs, she was depressed,

and yet she talked about it in a way we never hear – without

moaning. The first time I saw her begging, it was very difficult.

But filming her wasn’t so difficult because it didn’t

bother her. She didn’t see begging as demeaning or shameful

as she wasn’t “stealing anybody’s bread”.

Also, in the film, we take the time to meet her first, especially

in the sequence where we see her getting ready, doing her hair,

doing herself up, before seeing her begging, or as she says: “working”.

There is a lot of waiting in your film:

the uncertain waiting whilst begging, waiting for treatment, as

if time is crumbling...

Yes, because that is what their life is like. I needed to show

that rhythm, which is not ours. It’s as if they drift through

time that they can’t master. During filming, I was in that

temporality, asking myself the same questions as them: will they

manage to get health treatment, will they be deported or succeed

in finding work, will I manage to finish the film, will they go

back to Romania...

There are moments where the rhythm is more upbeat and Stella is

almost cheerful, such as during the French lessons, where she

is quite alert, even mischievous.

Stella is desperate to have friends and be in a social context

with people. During the French lessons, she is no longer a beggar,

no longer an Eastern immigrant, but a student, a person in her

own right. As a result, she gets her energy back.

With their return to Romania, the rhythm

picks up. The journey’s sequence is very short and when

she arrives home, she resumes the rhythm of a normal life.

For her homecoming, we used a process of ellipses. The time given

over to the journey in the film was the right one from the editing

point of view. It was important to follow her back to Romania

to understand where she comes from socially. She goes back to

her small two-roomed apartment, her neighbours, her family, her

memories, and her environment. And that is where I finally saw

her photo album...

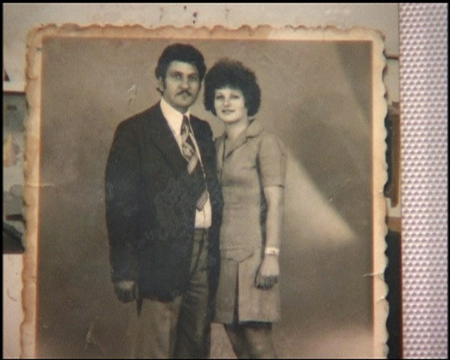

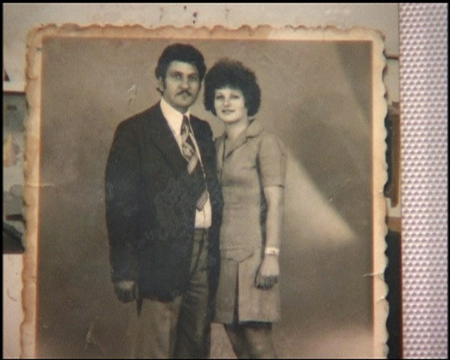

Right, tell me about the photo sequences...

When we look at her album, we see a whole chapter of her life

and her country’s history. I didn’t show them too

early on in the film as I didn’t want to make it too easy

for the spectators from the start in rendering Stella too nice.

I wanted to make the spectators work, confronting them with their

own prejudices and limits, before understanding her better. The

photos that take us back to Ceausescu’s era, when Stella

had stability and economic security are a way of rebuilding her

life story, and the life stories of so many Eastern immigrants...

Interview by Christine André,

for the Cinéma du réel 2007, international documentary

film Festival

Interview filmed for the Cinéma

du réel

Interview made by students of the Master

2 Image et Société, University Evry Val d'Essonne,

France. The extracts from this film, made by Mickaël Dal

Pra, Jean-Baptiste Fribourg and Julie Verger, will shortly be

on line on this site.

Stella, a history of Romania

Interview made by the French TV channel « TV

bruits », during the Résistances Festival, Foix,

France, july 2007-

See the video

Images: Hocine Kentaoui and Corentin Charpentier

Interview/editing: Corentin Charpentier Interview